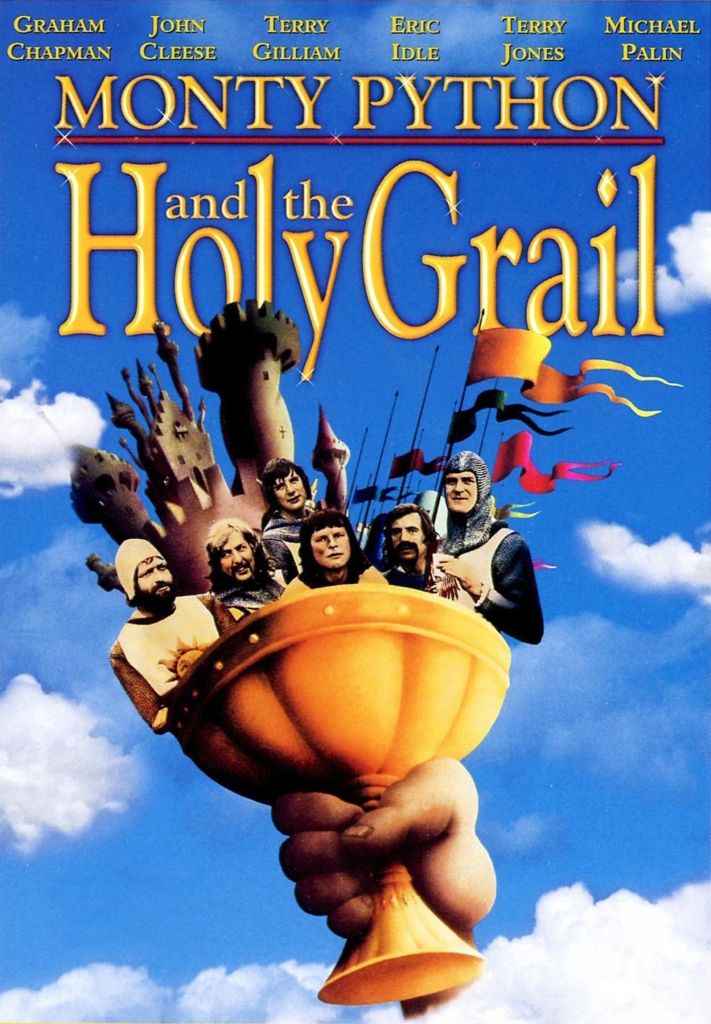

Monty Python and the Holy Grail hit theaters in 1975. Monty Python, already an established comedy troupe comprised of members Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, represented an innovative form of comedic story telling. The Holy Grail was the troupes first ‘proper’ turn to feature length films (the 1971 production of And Now for Something Completely Different was not an original script), directed by troupe members Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones.

If you haven’t seen it, the minimalist summary provided by imdb.com says it all: King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table embark on a surreal, low-budget search for the Holy Grail, encountering many, very silly obstacles.

My mom thinks I must have been about eleven or so the first time she watched Monty Python and the Holy Grail with me, and she still, twenty years later, likes to tease me for how very angry I was at the ending. You see, I was not prepared to understand the way the film moves between the modern and the medieval worlds, and the budget-friendly ending caught me off guard.

Eleven-year-old Eyan was FURIOUS with this ending. For the past hour and a half I had been transported to the silly castle Camelot and all that medieval Britain had to offer. And, while there were indications throughout the movie that perhaps all was not quite as it seemed, I was too young to fully understand the implications therein. The final police scene is set up early on, when we are shown what appears to be a historical documentary in progress.

Until one of the knights, I think it’s Lancelot, rides past at a full gallop, slashing the historian across the neck and opening the police investigation into the murder that culminates with Lancelot’s arrest and the closing scene of the film.

As a child, I was angry because I was ripped away from the medieval world and thrust back into the reality of modern-day behavior (even if “modern” in this sense was the film’s 1975 creation, and not the 2001 world I was watching from). As an adult, I appreciate the layering of the modern onto the medieval, and find the way that the Monty Python troupe handled their small budget by poking fun at the grail quest. You see, King Arthur never found the Holy Grail in literature, and in having the anti-climatic ending I now know and love, Monty Python was perhaps being more accurate than eleven year old Eyan could give them credit for.

In the 40+ years since the film’s release, medieval scholars have spoken about it at great length. You see, Terry Jones, one of the six original members of Monty Python, was also a medieval historian. In fact, the members of Monty Python were largely educated men, mostly having graduated from Oxford or Cambridge Universities in the UK, and generally had the background knowledge that can inform the subtle layering of meaning we see so often throughout.

What I love most about Monty Python and the Holy Grail is not its supposed accuracy as a piece of King Arthur’s enduring legacy, but rather, it’s ability to demonstrate both the concept of medievalism as well as the reminder that the vast Arthuriad (the collection of all literature and other media that make up the mythos of King Arthur) is huge and ever changing. Let me explain what I mean:

Medievalism is, more or less, this idea that can explain how modern audiences interact with the idea of the medieval world. So, we have a very broad definition for what is “medieval,” first of all. Basically, the British medieval period (because all countries have a different medieval period) refers to the period of time between Rome’s retreat out of Britain in about the mid 5th century and about Shakespeare’s time and the English Renaissance, the beginning of the 17th century. That is a HUGE period of time representing myriad cultural, language, and religious shifts in a country known for being invaded over and over again. What ends up happening, in the modern world, is this kind of condensed, culturally agreed upon, memory of the medieval. We associate chivalry and knights and peasants and the “dark ages” with the entirety of the medieval. So, anything created today in 2022, like the very recently released movie The Northman which tells the story of a Viking Prince seeking revenge for his father’s murder, that shows somthing medieval would be medievalism. It’s content that was created based on our idea of the medieval, but isn’t medieval itself.

King Arthur, too, is more complicated than you’d initially think. Was King Arthur a real man? Well, if you ask my undergraduate mentor and the medievalist that got me on my current trajectory, Dr Sweeney, yes, absolutely he was, and how dare you imply otherwise? He’s even got a tomb in Glastonbury:

We just can’t prove he was real. I don’t think it’s important whether he was or wasn’t, the story came from somewhere and what’s most interesting to me is the MYTH of him. So, that’s the Arthuriad. All the things you associate with Arthur, like the Round Table, Excalibur, etc., all come from different authors and points on the Arthurian timeline. The earliest tales of Arthur come from the Welsh, the well known stories of love and betrayal, the French. And yet all the pieces more or less fit together to create this caricature, and that’s what the members of Monty Python recognized so well in their own King Arthur.

Take for example, my favorite scene from the film:

Where to start? The Lady of the Lake? In Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, from the 15th century, includes the Lady of the Lake, but she first appeared in the French Vulgate Cycle (also occasionally known as the Prose Lancelot) 2 centuries earlier. Sometimes she is referred to as Viviane, as the French version of the Welsh title chwyfleian which had, at some point, been confused and conflated with the French figure Myrddin Wyllt, an early Merlin. She also sometimes becomes one with the Welsh figure Rhiannon, changing her name to Niniane and Nimue. Sometimes these names are all entirely separate women, sometimes they are the same, it depends on the author, the century, and what story is being told.

What makes medievalism fun, is that it doesn’t really matter who the Lady of the Lake really is. She’s a character that we immediately associate with King Arthur and Excalibur, so it works to name drop her in this scene as the means for Arthur’s assumed power. Of course Denis offers the modern rebuttal to such systems of power: “if I went around sayin’ I was an emperor just because some moistened bint had lobbed a scimitar at me they’d put me away!”

I think Monty Python and the Holy Grail’s continued success owes itself to the medievalism at play. They clearly didn’t take themselves too seriously as comedians, and while the interviews and documentaries released in subsequent years paint a fairly bleak picture of the filming process, by and large the removal of specific literary examples allows for the suspension of belief throughout.

I’ll close, not having discussed a myriad of things within the film that I could certainly wax poetic about but perhaps will save for later, with the final scene of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in homage to the angry and confused eleven year old I once was, having come full circle in the past 20 years to Arthurian scholarship in my own right, and a healthy dose of respect for the absurd.

Leave a comment