I have spent a lot of time analyzing individual words within a text to better determine meaning; it stands to reason that I am therefore interested in, or at least familiar with, the different ways in which transcription, translation, and adaptation can change the original meaning of a text. To illustrate this point, lets look at a text with many of all three, Beowulf.

Beowulf‘s narration takes place in 6th century Scandinavia, though scholars remain unconvinced when it was originally composed. The manuscript itself, of which only one has survived the perils of time, is undated, adding to the difficulties of properly dating such a document.

In brief, the 3000 lines of the Beowulf poem tell the story of the hero Beowulf as he attempts to save Danish King Hrothgar’s grand Heorot Hall from the murderous Grendel. Having defeated the monster early on, Beowulf gives Grendel’s arm, torn off during a grapple fight between them, to be displayed at Heorot Hall. The next night, however, Grendel’s mother comes from the large body of water nearby, seeking revenge for her son’s death. Beowulf fights her, too, following her down into the water where he finds the sword with which he kills her and beheads the corpse of her son, returning to Heorot in victory and acclaim. After this he returns home, becomes King of his own people for fifty years, until a dragon begins to terrorize his people. Beowulf, now very aged, nevertheless fights with the dragon, despite the desertion of all save one of his men. He and his remaining courtier slay the dragon, but only after Beowulf receives a fatal blow. His death marks the end of the tale, but not without the worried commentary of his people now they have lost a strong King to defend their borders.

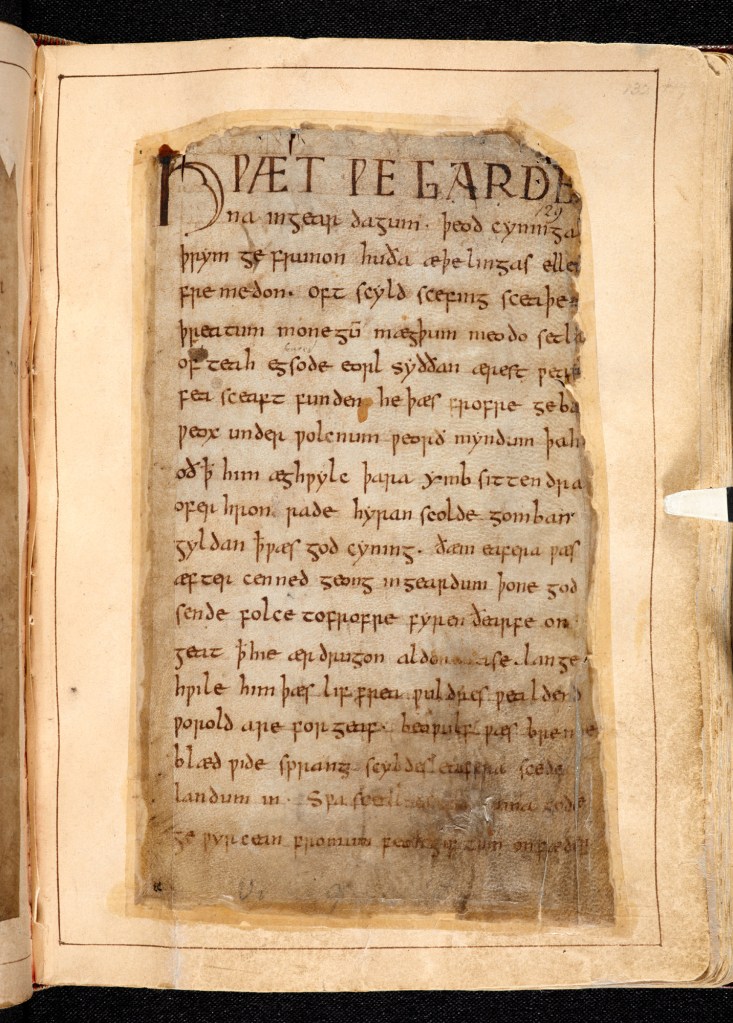

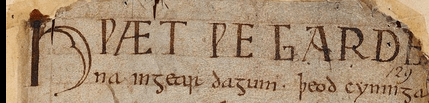

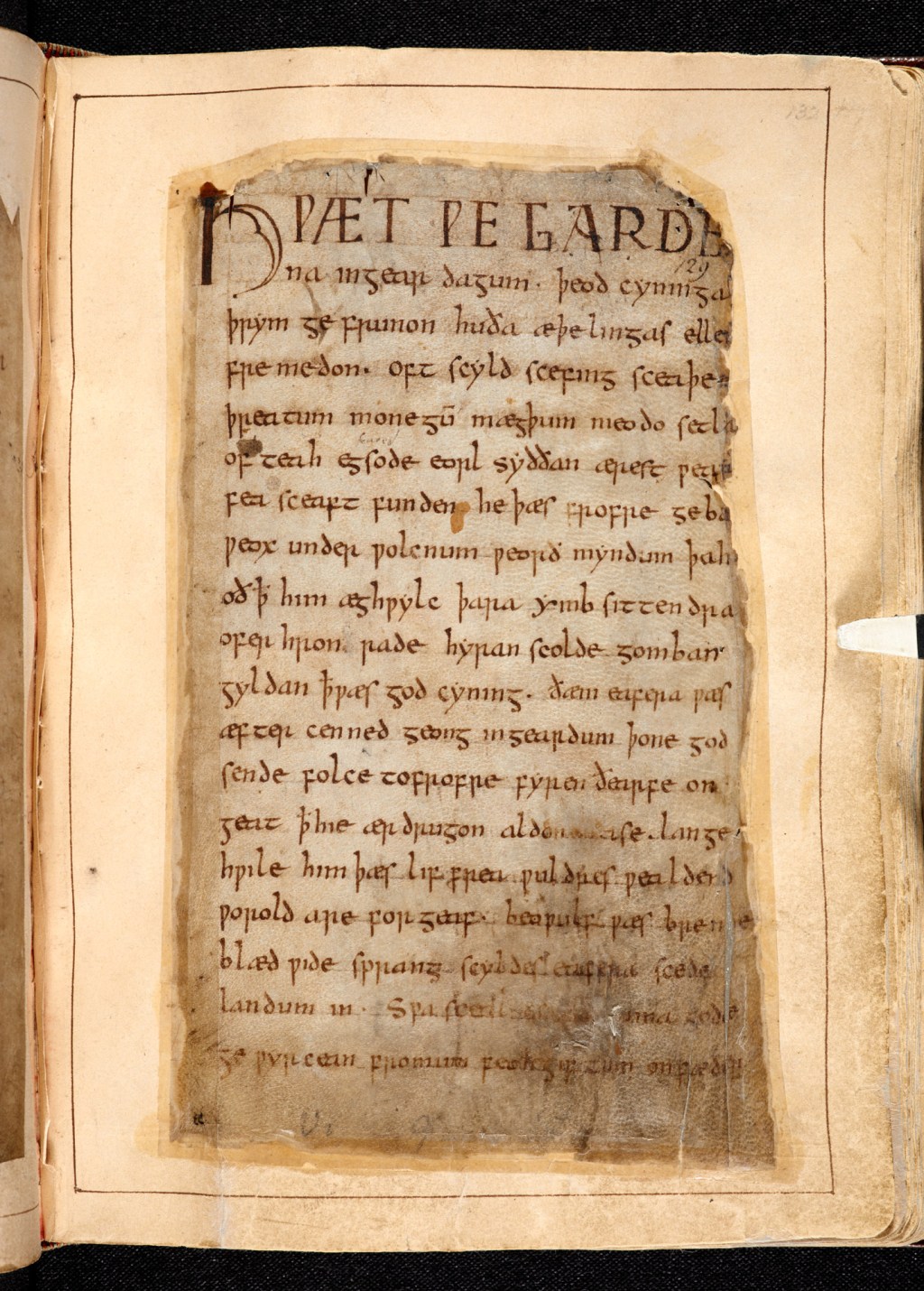

The above photo comes from the British Library’s digital manuscript collection, and shows the first page of text in Beowulf. The original manuscript itself is comprised of the smaller, darker, piece within the larger page; the manuscript was placed into paper frames as a preservation attempt in 1845. You’ll notice the script is clear and fairly legible, if you were able to read Old English, that is. In particular, the opening lines appear to be comprised of recognizable letters; a, t, e, r, and even d seem to appear on a first glance. And herein is the first trouble: transcription.

Before any work can be done with the text of Beowulf, the text must first be known. For such a well-known and fragile text, a scholar would not necessarily want (or be granted permission to) access the original manuscript itself, and could rely on a transcription done by a scholarly source. Recording exactly what the manuscript itself says, complete with any spelling errors, perceived exclusions or inclusions, and other notable elements would be the first step. You might imagine how, over the years, it can become very difficult to tell the difference between a “typo” and an intentional mark. This is especially tricky when only one manuscript survives, there is no second Beowulf to compare to.

And then we come to translation. Beowulf, as I said before, was written in Old English. This is the earliest form of English that can be pinpointed, though it is not readable by speakers of modern English without other language training. In general it was spoken in what is now England from about the 5th century to the Norman Conquest of 1066, brought by the Anglo-Saxon settlers and invaders.

As anyone who speaks more than one language knows, though, it isn’t a precise science to move between one language and another. Old English, while a precursor to modern English, has heavy Germanic influences, as well as inclusion and loan words from the scholarly Latin, and Old Norse languages. Many of the letters used in the writing of Old English have fallen out of modern use, as well, which adds to the complexity of translation.

Hwæt!

Let’s look at the opening lines to Beowulf, from the manuscript image above:

I am terrible at manuscript transcription, it was my worst class during my MA program; luckily Beowulf has an open access transcription provided through a joint project of the British Library and the University of Kentucky, and can be found here. It’s a fascinating thing to look at it, even if I can’t read Old English without a lot of help from the dictionary. Anyway, the top line through the large gap in the middle of the second reads as:

Hwæt we gardena in geardagum

transcription from the Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43521/beowulf-old-english-version

I LOVE the word hwæt in part because of its difficulty to translate into the modern English. A quick perusal of the word’s entry on the Oxford English Dictionary Online reveals a myriad of definitions, similarly linked, through the use of question asking. hwæt can ask identity, like the word what; an attention grabber, such as listen; and in general functions both as a “proper” form of speech, and colloquial, or slang.

Every time an editor puts together a new translation of Beowulf, they determine for themselves what kind of words to use. Since the 19th century, Beowulf has been translated into modern English over 50 times. Translations of hwæt include “Listen!” “Lo!” “So.” “Attend,” and “Behold.”

The Poetry Foundation’s online translation opts for “lo,” as did J.R.R. Tolkien and a number of others, rendering the opening lines:

Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings / of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50114/beowulf-modern-english-translation

While Irish poet Seamus Heaney’s 1999 rendition begins:

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by / and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness

Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. W.W. Norton and Company, 1999.

And then came Maria Dahvana Headley. Her first foray in Beowulf texts came from the publication of her 2019 novel The Mere Wife. This novel is an adaptation, not a transcription or translation, which means it is more inspired by than a direct result of. Headley’s novel tells the story of two mothers and their sons, each representing at turns Grendel and his mother, while mirroring back to each other those qualities which perhaps should be left unsaid. It is modern in its setting, but the suburban community of Herot is not, as Gren and his mother learn living on the outskirts of civilization, necessarily a beacon of all that is good in the world.

Her next project, logically, was a return to the text of Beowulf itself, culminating in the publication of her own, admittedly non-scholarly, translation last year, Beowulf: A New Translation, and it starts magnificently:

Bro! Tell me we still know how to talk about Kings! In the old days, everyone knew what men were: brave, bold, glory-bound.

Headley, Maria Davahna. Beowulf: A New Translation. FSG, 2021.

And here, finally, is the crux of it: What makes one of these translations any “better” than the others? If the intent of Beowulf in its inception arose from the oral story telling tradition, as many scholars assert, then the significance of the attention-grabber hwæt should not be lost in translation, and the use of attention-grabbing words can certainly change through time, as Headley’s version illustrates.

Does an adaptation such as Headley’s Mere Wife, in splitting Grendel and his mother into two sets of mother-son pairs while focusing on the maternal fierceness found in both women, is the impact of the warrior-hero Beowulf’s tale lost? Or is it just changed, so a modern audience with modern ideals can understand the competing loyalties heroic men must have been under?

Even with this single example it’s possible to see the range in definition and meaning that a solitary word can have on a complete text. Add in generations of scholarship, multiple languages, and differing models of critical theory, and it’s no wonder that there is no single consensus for any meaning lurking inside Beowulf. Is Grendel a monster in form, or is his monstrosity a metaphor for behavior?

Beowulf is a fantastic story of a hero and of monsters, where the line between magic and reality is blurred, even in terms of the medieval. How do Grendel and his mother survive at the bottom of the mere, for starters, and how does Beowulf survive the depths when he follows Grendel’s mother (who has no name or title of her own, save her relation to her son) home? Each adaptation adds something and loses something from prior attempts to encapsulate Beowulf in its entire historicity, and each translation is likewise colored by the biographical data of its editor.

So, how to choose a translation for hwæt? Well, what’s the impact, what’s the story? Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf emulated Irish Nationalism, J.R.R. Tolkien’s was an ode to the medieval world he studied so extensively, and Maria Headley’s two offerings? Perhaps a feminist twist to a monstrous angle.

Final Thoughts

I want to ensure that the take away from this conversation is not that words have little importance. Words, and which words we choose to use, can have a great impact. When analyzing literature, especially literature produced by authors long dead and gone, there can be a level of separation between intent and impact. I do not believe that to be the case in modernity, though.

Which words we chose to use to express ourselves matter to us, and to some level we all understand the concept of code switching-we wouldn’t speak in the same tone to a boss as we would to a child, for example. You can text less formally than you can send a work email, and you can probably send those emails less formally than you can write an essay or work report. We know that there are words and tones that apply to certain scenarios, and we move between them subconsciously, for the most part.

But I do want to encourage everyone to consider the ways in which words are used to cause great harm to marginalized groups every day. In the guise of “protection” larger and larger restrictions are placed on the bodies, behavior, and access marginalized people have to safety and security, to say nothing of familial or social acceptance.

Words matter, because words are how we interact with the world around us. When words are used to harm, how does that person regain safety? When words are misappropriated by the ill-intended, do we ignore the connotation in favor of a selfish desire to use a specific word that we have evidence causes harm? There are over 171,000 words in modern English, surely we can be more clever, more creative, and more kind than to perpetuate the use of gendered, stereotyped, racist, harmful words.

Leave a comment