Perhaps the strangest side effect of studying medieval literature, for me personally, is the way in which I interact with all media has significantly changed. I will be the first to speak about my struggle with intense anxiety and imposter syndrome, even writing this very informal blog causes me concern, so it follows that I would also have experienced embarrassment from time to time. Now, it used to be because I thought there were “acceptable” things to like and spend my time on, and the unacceptable. Certain genres were not scholarly and therefore not “real” reading, ranging from fantasy to science fiction to mysteries and beyond. But no genre has been so maligned both inside the academy and in the court of popular opinion as romance.

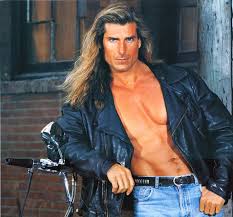

When I say Romance, you might think about Fabio, as pictured above on a 1997 poster from the American Library Association’s push to encourage leisure reading through the late 80’s and 90’s. This is certainly the bulk of modern romance as a genre: a book where the plot focuses on the romantic relationship between two people, and probably has a happy ending either with a marriage or the consummations/continuation of a significant relationship. There’s this prevalent idea that romance is “chick lit”, aka, written by women, for women, without the level of depth or characterization expected in other more “academic” genres. This is ridiculous. You can certainly have a preference for not enjoying romance, but to categorize the entire genre as patently non-academic, and by extension, non-valuable, is a mistake. The inclusion of romantic relationships does not devalue the plot in any way by its existence, and while not every book needs to be layered with subtext and space for analysis, to discount romance simply on the assumption that ALL or even the vast majority of such books lack any kind of depth is rooted in misogyny.

Medieval Romance

Romance, in its initial creation, came from the medieval period. What set these stories apart from other writing of the time began with the language used. You may have heard languages such as French or Italian referred to as “romance languages” and that is because of their origin. Romance languages stemmed from the Latin used in scholarly writing at the time, and when authors began writing, not in Latin, but in their mother tongues, the association between using romance languages and romance as a genre began.

Medieval Romance as a distinct genre also followed specific structures and plot points. Dating back to the twelfth century French author Chrétien de Troyes, the established characters of the chronicle tradition, like King Arthur, found themselves in the dramatized courtly narratives of early romance. Romances often were stories of Knights and Kings overcoming great odds, with questing and adventure, and the winning of beautiful ladies through feats of prowess and ability. There was always a “happy” ending, or at the least, the consummation of a relationship and the return of all characters to the “proper” social order.

There has long been a focus on love as a romantic and sexual force between two people in romance literature. Prior to the creation of the genre, the vital relationships in question were homosocial, between two men. The genre of the day had been, also from the French, the chanson de geste (song of heroic deeds), narrating the deeds and adventures of great men, often loosely based on historical personages such as Alexander the Great. The deeply emotional bonds between men were demonstrable and melodramatic in this tradition, with much less emphasis on the consummate heterosexual relationship that sometimes would occur for the primary hero.

By contrast, while romances still focus on the deeds of great men, much more emphasis is placed on the courtly love aspect. Marriage was a contract between two families, where the dowry a bride could bring her husband, as well as the noble lineage that their children would carry, played a far more important role in finding a spouse than the feelings of those involved. Courtly Romances allowed for love to become part of the narration, within a very specific pattern.

Genre and Structure

Courtly Romances and Courtly Love operated within this loose structure: A man, who was either already a knight or soon to become one, would become enamored with a beautiful lady. His feelings of passion could completely undermine his ability to function, eclipsing everything except for his attempts to woo this lady. Lovesickness, in this era, was thought to be an actual malady, reducing manly men to emotional wrecks, incapable of returning to their masculine endeavors until they could purge the lovesickness from their bodies. In order to do so, he could approach the lady to profess his love. If she acquiesced, she could assign him a quest or task to prove his worth as a knight and lover. These quests were often mystical, impossible, and rife with the magical influence found throughout medieval literature. Successful completion of the quest allowed the man to win the lady, and they could then wed.

Of course, sometimes the Lady was already married. In courtly romances, the love between knight and lady was privileged as the “proper” example of love, as the fin d’amor, or true love (also sometimes called simply “courtly love”). This love gave narrative space to ignore the sin of adultery; ignoring your true love was a far greater transgression. Though, the sexual consummation of these love matches was often not explicitly included in the text itself; if no sex was written down, then no adultery could have been proven.

It is clear to me the emphasis on love relationships was born from a societal interest. In the medieval period, a large majority of marriages were made as contractual obligations. The higher in class, the more likely to be involved in an arranged and beneficial marriage. In fact, the predominating idea that marriage is and should be born from love matches is relatively modern, gaining traction for lower and working class people during the Industrial Revolution, and increasing into the noble classes as time continues forward.

If the people reading medieval romances had wed for convenience, money, contract, alliance, etc., then the overwhelming power of fin d’amor must have seemed so very exciting. The flip side, however, was the profound effect love sickness was supposed to wreck on those too weak to control themselves against it. To be love sick was to be sick, and often men in these early romances experience a bout of madness or insanity brought on by their deep and passionate love. As a literary trope, it could be used to illustrate depth of emotion, instability, and unrequited passions, which could enhance or debase the character of the man in question.

Into Modern Romance

All this said, it makes sense that romance, both as a genre and a theme, remains prevalent in modern literature, with a rich background full of space for analytical depth and context. As a structure, they can be comforting: no matter how tragic the middle parts are, the expectation is a happy ending and consummated relationship. They can be a form of escapism, albeit one that has become socially unacceptable through the years, as the focus on the female half of these relationships rose to prevalence.

So, too, did contemporary feminist and sexual liberation movements add to the content of the genre. The shift away from desperate longing tempered with chaste kisses and into scenes of sexual desire, both imagined and acted upon, likely contributed to the shift in social acceptability, never mind the increasing detail and explicit descriptions gaining popularity in novels of other genres. Novels of the 20th century that are considered academic, and classics of the literary canon, with included sex scenes include:

Is it the association with female sexuality that renders contemporary romance so unpalatable for the academy and/or the ultra-masculine? Is it the creation by and marketing to women, by and large, some sort of signal that to associate with it would then render you likewise a woman? Whatever the subconscious psychological and social contexts that have given rise to this idea that romance=lesser, it is clear to me that it is unfair and untrue. You don’t have to enjoy love as a plot, you don’t even have to enjoy romance as a genre, everyone has their own likes and dislikes. I would, however, encourage you to broaden your horizons by trying something new. I would also think about why romance tends to be avoided.

The PhD proposal I submitted to the University of Birmingham (pending, I do not have a response yet but they’re working on it and I have 1 advisor that would take me, need a 2nd) involves the shift into fantasy romance in the early 2000’s. I want to explore the link between fantasy romance and medieval romance as a means to analyze gender and sexual roles inside medievalist texts. The two series I mention in this initial proposal used to be guilty pleasures. I love these authors, but I never wanted to admit it, for myriad reasons. But I do believe in retrospect a lot of my perceived discomfort was in the social connotations of enjoying such novels. I refuse to feel guilty for reading what I enjoy, anymore, though. I can, and do, interact with literature as best as I can, to ensure I’m noting the problematic moments or authors, and I think this proposal would allow me to do that kind of work on these well-loved books.

Final Thoughts

The books in question can be found in the gallery below. I don’t want to go into too much detail about this proposal until I know what’s going on with it, so I’ve made a list that includes the books I reference specifically, books I thought about including, books I might still talk about, and others that I am trying to not label in my own mind as guilty pleasures.

Leave a comment